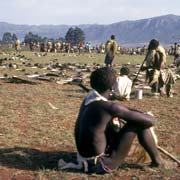

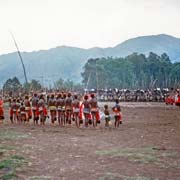

Photos of the iNcwala or First Fruits Ceremony in 1970, Swaziland

The iNcwala or First Fruits Ceremony in 1970

The iNcwala is the most important ceremony of the Swazi people. It usually takes place in December and, among other things, it affirms the Swazi identity and its kinship with the King. It signals the end of the old and the beginning of a new year when the first fruits of the new harvest may be eaten.

you may then send it as a postcard if you wish.

During the iNcwala the whole nation is involved, with groups of men (called "bemanti", people of the water) walking to the different rivers and also the sea in Mozambique to collect water that will be ritually used later. There are various preliminary rituals that are known as "iNcwala lencane" (Small iNcwala).

The "iNcwala lenkhulu" (Big iNcwala) starts off when groups of young men set out from the Royal capital of Lobamba to collect "lusekwane", a species of acacia that will be used to cover the "inhlambelo", the sacred enclosure in the "sibaya", the cattle kraal, where most ceremonies will take place. The men and boys who bring back the lusekwane must be "pure", meaning not yet having had sexual relations; if they had, their lusekwane would wilt when they bring it back and they would be the butt of jokes. They march with the "emabutfo", warriors regiments to the Royal residence of Lozitha first. All the way they sing a specific iNcwala song that is strictly taboo any other time of the year. Entering Lozitha the warriors give the Royal salute, in which they emit a piercing whistle while raising their large cowhide shield ("lihawu") above their heads. They dance and surge forwards, towards the King and other members of Swaziland's Royalty.

Later the men set off from Lozitha in a long file, loudly singing the iNcwala song. Towards dusk they reach the areas where the lusekwane grows and collect the shrub in the middle of the night; they then return to Lobamba where they arrive at daybreak, still singing the specific iNcwala song. They have a rest and, after a dance followed by a surging forward of the "emabutfo", the traditional regiments, the warriors leave their shields and also go for breakfast.

The young men and boys then march with their lusekwane shrubs towards the "sibaya", the cattle byre, that is the focal point of the ceremony. They loudly sing the iNcwala song and there is an element of show here, where young men try to impress by the size of the lusekwane they have carried all the way from where they cut it; there are almost whole trees among them. The girls especially watch them of course and notice if the lusekwane has wilted: a sign the boy carrying it has not been that "pure". Some ribald joking may be made at his expense. In the "sibaya" they throw their lusekwane on a pile at one of the walls. Old men will later use this to cover the "inhlambelo", the enclosure where the King will undergo certain rituals on the main day of the ceremony. The Swazi warrior regiments, men and boys, keep singing and dancing in the sibaya until late afternoon.

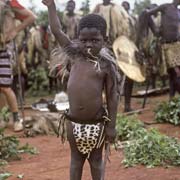

The day after the bringing of the "lusekwane" shrub, leaves ("emacembe") of the "mbondvo" shrub are collected locally around Lobamba. This is an opportunity for the younger boys, for whom gathering of lusekwane is too strenuous, to participate in the ceremony. So it is mainly young boys who collect bundles of leaves that will be used to cover the lower part of the "inhlambelo" sacred enclosure, so that the private ceremonies performed by the King will remain private. The boys collect the leaves and walk with these towards the "sibaya", the cattle byre; they then enter the sibaya, throw their bundles of leaves down and run away, some emitting piercing whistles. The old men gather the leaves to use them later. Different groups bring those leaves, accompanied by groups of warriors with shields.

After this a ritual slaying of a black bull takes place: the young men strip to their "emajobo", the skin loin covering they wear; although normally very young boys just wear an "emajobo", when they get older they wear "lihiya", a wraparound piece of material underneath it for modesty. But in this ritual only the skin covering is worn; a black bull (actually an ox) is released, the men run towards it, grab it by the horns, and, loudly singing the iNcwala song, drag it to the enclosure that was built from the lusekwane shrub. They then kill it with their bare hands. Body parts of this bull ("inkunzi") will be used on the main day in the King's rituals. The young men later march in triumph, still singing the sacred iNcwala song....

Early in the morning on the Main Day the King performs rituals in the enclosure and at its climax eats of the First Fruits. That day almost the whole nation comes to the Royal capital of Lobamba where in the huge "sibaya" or cattle enclosure the ceremonies are held. People will now be dressed in full iNcwala costume, which includes, for the men, a "siketja", a kind of cloak made from horse tails. The "emabutfo" or traditional Swazi regiments march in, singing as they go. In Lobamba there are various "emalawu", enclosures of different regiments or age-grade groups, each with traditional grass beehive huts, where they can stay. The Regiment of His Majesty King Sobhuza II was the Balondolozi regiment, the most senior; the next in seniority (age grade) was the Emasotsha regiment. The men are getting ready, some donning headdresses of black feathers of the "sakabula" bird.

After a "reveille" blown on a trumpet or cornet (traditionally a conch shell, brass instruments were first brought to Swaziland by men who had been working in South Africa) the regiments enter the "sibaya" and start their stately dances, accompanied by singing the ancient songs, the warriors dancing slowly, each holding a "sakila" or knobkerie fighting stick or "lizeze", battle axe and their "lihawu", large shield. The King's sons are only distinguished by the red feathers they are allowed to wear in their hair. The "batfwabenkosi", ("children of the King") or Princesses enter, the unmarried girls dressed in "indlamu", a short skirt decorated with beads and the married women in full "sidvwaba" skin skirt; they dance in a line opposite the warriors. Then the King himself arrives, accompanied by other members of the "Balondolozi" regiment and takes his place among the other regiments and joins in the dance.

A stage has been built for visitors to sit and observe the ceremony. Pots of "tjwala", fermented maize beer, are prepared for participants and guests. During the day more and more people arrive and eventually there are hundreds of warriors dancing the slow dances. Towards late afternoon the king, accompanied by members of his "Balondolozi" regiment leaves, but the dance continues without interruption. Tjwala is offered to the visitors. At sunset the regiments finally march out, each giving the piercing whistle, the Royal salute, while lifting their cowhide shields over their heads.

A few days later the final day of the ceremony takes place. Early in the morning, in the sibaya, the King washes himself with water from the various rivers and the sea, carried in dishes by boys accompanying him. A fire is made and the remains of the bull, uneaten fruits, last year's bedding and clothing used by the King is ritually burnt. The regiments again dance and the King joins them for a final dance. The fire is expected to be extinguished by rain and this usually happens! The iNcwala ceremony then comes to an end: the nation is renewed and its kinship with the King is reaffirmed.

See also: the iNcwala ceremonies in 1974.