Photos from Tibet

| Home | About | Guestbook | Contact |

TIBET - 2023

A short history of Tibet

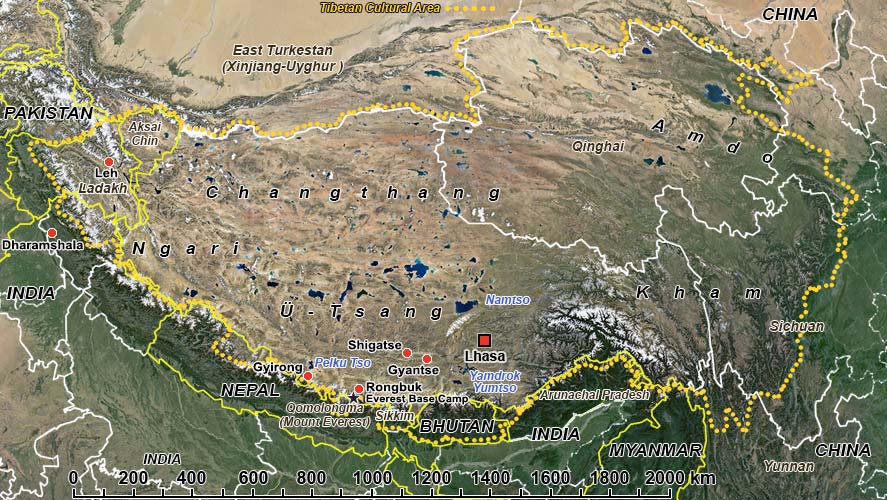

Tibet, or Greater Tibet, is a region in the central part of East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about 2,500,000 km², the homeland of the Tibetan people. Since the annexation of Tibet by the People’s Republic of China in 1951, the entire plateau has been under Chinese administration, and a considerable number of Han Chinese and Hui have settled here. Tibet is now divided administratively into the Tibet Autonomous Region and parts of the Qinghai and Sichuan provinces. It is the highest region on Earth, with an average elevation of 4,380 metres, with Mount Everest, Earth’s highest mountain, rising 8,848.86 metres above sea level. The Tibetan Empire emerged in the 7th century with the rule of Songtsen Gampo (604–650 CE), and at its height in the 9th century, extended far beyond the Tibetan Plateau, from the Tarim Basin and Pamirs in the west to Yunnan and Bengal in the southeast. It then divided into a variety of territories. The bulk of western and central Tibet (Ü-Tsang) was often at least nominally unified under a series of Tibetan governments in Lhasa, Shigatse, or nearby locations. The eastern regions of Kham and Amdo were divided among several small principalities and tribal groups, which usually maintained a more decentralised indigenous political structure while often falling under Chinese rule. Most of this area was eventually annexed into the Chinese provinces of Sichuan and Qinghai. The current borders of Tibet were generally established in the 18th century.

The Mongol Yuan dynasty (1271-1368) ruled Tibet through a top-level administrative department. Tibet retained nominal power over religious and regional political affairs, while the Mongols managed a structural and administrative rule over the region, reinforced by rare military intervention. It ended with the Ming overthrow of the Yuan and subsequently by the Qing, who took control of Tibet in 1724; eastern Kham was incorporated into neighbouring Chinese provinces in 1728. Meanwhile, the Qing government sent resident commissioners called Ambans to Lhasa. Like the preceding Yuan dynasty, the Manchus of the Qing dynasty exerted military and administrative control of the region while granting it a degree of political autonomy. However, the Qing dynasty weakened, and its authority over Tibet gradually declined. In 1904, Sir Francis Younghusband led a British expedition into Tibet. Initially, it aimed to resolve border disputes between Tibet and Sikkim, but it quickly became a military invasion. The British expeditionary force, consisting of primarily Indian troops, invaded and captured Lhasa, with the Dalai Lama fleeing to the countryside. Afterwards, Younghusband negotiated a Convention, guaranteeing economic influence by the British but ensuring that the region remained under Chinese control. In 1910, the Qing government sent a military expedition of its own to establish direct Manchu-Chinese rule and, in an imperial edict, deposed the Dalai Lama, who fled to British India. The Chinese mistreated civilians and disregarded local culture, so following the Chinese Revolution and overthrow of the Qing dynasty in 1912, Qing soldiers were disarmed and escorted out of the Tibet Area (Ü-Tsang).

The Dalai Lama refused any Chinese title and declared himself ruler of an independent Tibet, although the Republic of China still claimed the country as the “Tibet Area”. In 1913, Tibet and Mongolia concluded a treaty of mutual recognition, although the subsequent Chinese Republican government did not recognise this. Later, Lhasa took control of the western part of Xikang, the western Kham region populated by Tibetan people, called Khampas. In 1914, the Tibetan government signed the Simla Convention with Britain, which recognised Chinese suzerainty over Tibet in return for a border settlement: the nominal Xikang province included in the south the Assam Himalayan region (named North-East Frontier Agency, now the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh). Tibet had recognised this as a part of British India by signing the Agreement in 1914, recognising the “McMahon Line” as the border. China refused to sign the Convention and still claims what it calls “South Tibet”. In the Sino-Tibetan War of 1930–1932, the Tibetan army under the 13th Dalai Lama invaded the Chinese-administered eastern Kham and the Yushu region in Qinghai. Tibet claimed those regions, being almost wholly inhabited by Tibetans; they easily defeated the Chinese, but the Chinese Republic sent reinforcements under Chiang Kai-shek. Eventually, the Tibetans were defeated because of China’s massive military superiority. The British government - and, later, India - provided some military training and small quantities of arms and ammunition to Tibet throughout the 1912–1950 period of de facto Tibetan independence, but it was never enough.

On 6 July 1935, a boy called Lhamo Dhondup was born in Amdo, eastern Tibet (but in Chinese-administered Qinghai Province). He was recognised by all concerned as the incarnation of the 13th Dalai Lama, a title going back to the 14th century, given by the Tibetan people to the foremost spiritual leader of the Gelug or “Yellow Hat” school of Tibetan Buddhism. The incarnation had to be approved by the Chinese government, often with a drawing by lots (the Golden Urn), introduced during the Qing dynasty, in which the emperor or his officials would have the final say. It was dispensed with this time, and the boy was released by the (Muslim) warlord ruling Qinghai after Lhasa paid a ransom of 400,000 Silver Dragon coins. Lhamo Dhondup travelled to Lhasa in 1939 and was enthroned as the 14th Dalai Lama by the Tibetan Ganden Phodrang Government. A Chinese delegation was present, and a huge portrait of Dr Sun Yat-sen, the founder of the Chinese Republic, and a Kuomintang flag had to be displayed in the monastery’s main hall. In the 1940s, Tibet altered its position on the McMahon Line. In late 1947, the Tibetan government wrote a note presented to the newly independent Indian Ministry of External Affairs laying claims to Tibetan districts south of the McMahon Line. It sent a delegation to the Asian Relations Conference in New Delhi, India, representing itself as an independent nation under its flag. India recognised Tibet as a de facto independent nation from 1947 to 1954, when India and China signed a trade agreement. Tibet had also sent trade missions to China, Hong Kong, the US, and the UK, although none of those supported Tibet’s total independence from China.

In 1949, China fell to the Communists, and to prevent agitation in Tibet by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the government expelled the (still Nationalist) Chinese delegation in Lhasa. Even before the People’s Republic of China (PRC) was proclaimed in 1949, the CCP had declared that Tibet (and Taiwan) would be incorporated by any means. As it seemed likely Communist China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) would invade Tibet to “liberate” it from its theocratic feudal system, the Tibetan government belatedly started to modernise its army. Still, the million-strong PLA would heavily outgun them, battle-hardened from the Chinese Civil War. Appeals for international support to protect Tibet only resulted in some small arms aid and military training. Still, months of failed negotiations and attempts by Tibet to secure foreign support and assistance led to nothing. And then the nightmare began. In October 1950, on the first anniversary of the establishment of the PRC, 80,000 PLA soldiers crossed the Jinsha (Yangtse) River into Tibet. After heavy fighting, they captured the town of Chamdo (Qamdo) in the southeastern region of Kham, where the Tibetan Army’s Commander-in-chief was Ngapo Ngawang Jigme (who would later sign the “Seventeen Point Agreement”). It was reported that 114 Chinese and 180 Tibetan soldiers were killed or wounded. India signed a protest, and Tibet appealed to the United Nations, but, not being a member, nothing happened. Chinese propaganda proclaimed that “Tibet had been peacefully liberated”. Meanwhile, in Amdo, the region in the northeast had been infiltrated by communists who severely restricted the monks in their monasteries and sent Takster Rinpoche, the older brother of the Dalai Lama, to Lhasa to persuade him to accept Chinese rule. Instead, he told the Dalai Lama what Chinese rule had turned out to be and fled abroad after failing to persuade his brother to go too.

On 17 November 1950, the Dalai Lama was formally enthroned in an elaborate ceremony. He was only 15 years old, but people felt he needed the authority to deal with the situation. In February and April 1951, Tibetan delegations went to Beijing to conclude peace talks, which ended in the “Seventeen Point Agreement” between Tibet and the PRC on 23 May 1953. It was a blatant piece of Chinese sloganeering, with, for example, its first point proclaiming that “the Tibetan people shall unite and drive out invading imperialist forces from Tibet; the Tibetan people shall return to the big family of the motherland – the People’s Republic of China”. There were no “Imperialist forces” operating in Tibet (the last time was the Qing Manchu army in 1912), and no Tibetans thought being a family member of a “motherland” and certainly not of this newly formed communist dictatorship. The people of Tibet and China are totally different in ethnicity, culture, language and script. On the contrary, Tibet had rights in parts of China, such as Qinghai and Sichuan, where the majority was ethnic Tibetan. But they had no choice, and this first point effectively meant annexation. The whole Agreement was signed under duress; Ngapo Ngawang Jigme, the leader of the delegation, was not permitted to communicate with Lhasa, from where they had been sent only to negotiate, not sign anything: the Dalai Lama had kept the government seals. The terms of this Agreement had not been cleared with the Tibetan Government before signing, and it was now divided as to whether they should accept the document as written or flee into exile. The 16-year-old Dalai Lama chose not to go into exile and decided to have no choice but to formally accept the “Seventeen Point Agreement” to prevent bloodshed.

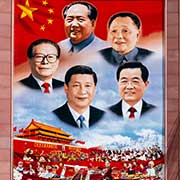

On 24 October 1951, General Zhang Jingwu, the head of the Chinese delegation in Lhasa, sent a telegram to Mao Zedong confirming support of the Agreement. Two days later, on 26 October, Chinese troops, 3000 men, marched into Lhasa, and a short time later, more soldiers, with red flags and large pictures of Mao. It meant the annexation of Tibet, officially known in the PRC as the “Peaceful Liberation of Tibet”. It was anything but: with 20,000 Chinese soldiers, Lhasa’s population almost doubled, and a food shortage developed. At first, the PLA seemed to honestly pay for food and lodging, as was part of the Agreement, but soon, they started making demands without payment, causing active resistance and growing hatred for the foreign occupiers. Despite this, the Tibetan government remained in place in the areas of Tibet that it had ruled before this annexation. The Dalai Lama even visited Beijing in 1954, meeting Mao Zedong (who told him “Religion is Poison”) and other Chinese leaders and observing industrial progress, which Tibet lacked at the time. Tibet was indeed a feudal and undeveloped country, and the Dalai Lama was acutely aware of this and eager to modernise society. They didn’t need or want others to do it for them, something the Chinese were now doing with brute force. In late 1955, the Chinese in the Amdo and Kham regions were forcing “reforms” on the people, taxes levied on houses, land estates, cattle and even monasteries. Monks and nuns were mistreated, humiliated in public and forced to kill animals, something totally against Buddhist doctrine. That winter, Khampa refugees started to arrive in Lhasa with the most terrible stories of bestial treatment and humiliation by the Chinese. People had been tortured in public and beaten to death, and sometimes, the victim’s children were forced to carry out the sentence.

In 1955, the Preparatory Committee for the Autonomous Region of Tibet (PCART) was formed as an interim governing body, which, on paper, seemed to the Tibetans an improvement over the Chinese Tibet Military Commission that often opposed the Kashag (Tibetan Government) and was viewed with hostility by the Tibetans. But almost all of the 51 delegates were handpicked by the Chinese. In Kham, people were called together and told that their farms would be turned into collective farms; most Khams objected and were called for a meeting in a fort near Chamdo. There, they were locked in, guarded by PLA troops and told they would only be freed when they agreed with the “reforms”. They managed to escape, forming a guerilla group fighting the Chinese. But some were caught, and a newspaper showed a row of hacked-off heads with the caption these were of “reactionary criminals”. The Khampa/Amdowa freedom fighters had some success resisting the Chinese oppressors, but the PLA was getting 40,000 reinforcements. They bombed the Lithang monastery in Kham, killing thousands of monks and ordinary citizens, followed by brutal tortures and executions of women and children whose fathers were involved with the resistance. There was disgusting mistreatment of monks and nuns; in public, they were forced to break their vow of celibacy and even kill people. When confronted by the Dalai Lama about the torture and bombings by the Chinese of the Tibetans, the answer was that “criticism was an insult to the motherland which only wanted to help and protect the Tibetan people and if there were a few people who did not want reforms - reforms that would only benefit the people - then it was logical that they were punished”.

By 1957, Kham was in chaos, with PRC-initiated land reforms and harsh reprisals against landowners under the justification of “freeing the serfs”. Resistance fighters’ attacks and PLA reprisals against Khampa resistance groups became increasingly brutal. A Tibetan guerrilla group, the Chushi Gangdruk, was formally organised in 1958. It included Tibetans from other regions and had the objective to drive Chinese occupation forces out of Tibet. The situation in Tibet became increasingly tense as many Tibetans began to support the Khampa uprising. The Tibetan government was in a bind: officially, it was adhering to the “Seventeen Point Agreement”, and in this situation, the government in Lhasa neither wanted to back a rebellion nor publicly oppose it, while the Chinese Communist Party put pressure on the Dalai Lama’s government to join the operations against the rebels and made it increasingly evident that a spread of the insurgency would lead to “all-out repression” in Tibet. Pressure by PLA generals on the Dalai Lama to comply and even for him to mobilise the Tibetan army against the rebels became ever more arrogant and insulting. In February 1959, the Chinese invited the Dalai Lama to attend a dance performance to celebrate his attainment of the Geshe academic degree, although he still had his examinations. There were also preparations for the important yearly Monlam Prayer Festival. The Chinese declared they would handle the Dalai Lama’s security and wanted him to attend without armed bodyguards. Members of the Kashag, the Tibetan Government, now feared the Chinese wanted to abduct the Dalai Lama, and this fear spread to ordinary Tibetans. On 10 March, thousands surrounded the Dalai Lama’s palace to prevent him from leaving or being removed. They demanded that he not attend this dance at the PLA headquarters; this marked the start of the uprising in Lhasa.

But there had already been skirmishes between Chinese forces and guerrillas outside the city in December 1958. The protests grew, with demands the Chinese must go and “leave Tibet to Tibetans”. The Kashag Tibetan government now legally repudiated the “Seventeen-Points Agreement” with the Chinese Government on 11 March 1959 and declared independence. The Chinese started to deploy artillery within range of the Norbulinka, the Dalai Lama’s Summer Palace. On 12 March, thousands of women gathered in front of the Potala Palace in Lhasa and demanded independence, now known as “Women’s Uprising Day”. On 14 March, thousands of women assembled in a protest led by Gurteng Kunsang, an aristocratic woman who was later arrested by the Chinese and executed by firing squad. On 17 March, two artillery shells landed near the Dalai Lama’s palace. Tibetan troops had already taken preparations in secret to secure an escape route from Lhasa, and the following night, disguised in a uniform of the Chinese Army, the Dalai Lama secretly left the Potala and slipped out of Lhasa with his family and a small number of officials. In Lhoka, southeastern Tibet, he linked up with Kham rebels who protected him, and he slipped over the Indian border on 31 March 1959 at Tawang in what is now Arunachal Pradesh. The Dalai Lama had sent a letter requesting asylum to the Indian president Nehru, who sent a detachment of the Assam Rifles to the border post to welcome him. He was escorted to Bomdila, 180 kilometres further on, where he could rest and recover from an attack of dysentery and stayed for a year in Mussoorie before settling in Dharamshala (Dharmsala), Himachal Pradesh, where the Tibetan Government in Exile was allowed to set up its headquarters.

The Chinese press claimed that the Dalai Lama had been pressured and kidnapped by “rebels” and continued: “The uprising of the Tibetan people was organised by a reactionary clique from the upper classes, but with the help of patriotic Tibetan monks and the public, the People’s Liberation Army completely suppressed the uprising, because the Tibetan people are very patriotic, support the Central People’s Government, love the People’s Liberation Army and oppose imperialists and traitors.” The reality was that oppression and terror by the Chinese became worse, and thousands of Tibetans tried to flee. After the first bombardments of the Norbulinka Summer Palace, shots were fired at the Potala and the most sacred Jokhang temple. Thousands were killed, and damage to buildings was extensive. It is not known how many people were killed in these massacres. There is a PLA document obtained by Tibetan freedom fighters in the 1960s that 87,000 people were killed in military actions between March 1959 and September 1960 (not counting all those who died by suicide, torture or starvation). Since that time, there have been further privations in Tibet: Mao’s disastrous “Great Leap Forward” from 1958-1962, with enforced agricultural collectivisation and industry, caused some of the worst famines in modern history. Then the “Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution”, launched by Mao in 1966 and lasting ten years, was characterised by violence and chaos, with “Red Guards” seeking to destroy the Four Olds (old ideas, old culture, old customs, and old habits), taking the form of destroying historical artifacts, cultural and religious sites: thousands of monasteries in Tibet were destroyed, monks and nuns murdered. Priceless ancient Buddhist libraries burned to the ground.

Finally, in 1965, the Chinese, who had already dismissed the Kashag Tibetan Government after the Tibetan uprising in 1959, established the “Tibet (or Xizang) Autonomous Region”, making Tibet a provincial-level division of China. China still claims Arunachal Pradesh, India, as “Zangnan” (South Tibet), invading it in 1962 during the Sino–Indian War, causing many casualties; it also claims areas in Bhutan and occupies the Aksai Chin region in Ladakh, India, which it overran in the same war. The Tibetan Government in exile and the Dalai Lama have again recognised the McMahon Line as the border between Tibet and India; in any case, people in Arunachal Pradesh don’t want to be part of a Communist Chinese-ruled Tibet. There have been more and more restrictions on Tibetan society; some monasteries of the thousands destroyed or damaged have been restored, and there are monks, but far fewer than before the Chinese occupation, and authorities closely watch them; it is now almost impossible for young people to join. An estimated million Tibetan schoolchildren are now compelled to attend Chinese-language boarding schools away from their homes, raising fears that their own language will soon disappear, and they are brainwashed with the official history of the events. In 1989, the Dalai Lama was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for advocating peaceful solutions based upon tolerance and mutual respect to preserve the Tibetan people’s historical and cultural heritage; his major concern is the massive influx of Chinese settlers into Tibet. China reacted furiously: it is strictly forbidden to have an image of the Dalai Lama, who is denounced as a “splittist” wanting to split Tibet from the “motherland”, and so is the Tibetan flag: only the red flag of Communist China is displayed. It is clear the Chinese still fear the real feelings of the Tibetans. Chinese propaganda is that Tibetans are grateful to be “liberated”. But between March 2009 and 27 May 2012 (when two young Tibetan men set themselves on fire in front of Lhasa’s Jokhang temple), there were 35 Tibetan self-immolations in protest against Chinese rule and restrictions, many of those in Tibetan-populated Chinese provinces.

Foreign tourists may visit Tibet only with a special permit and on guided tours. More and more Han Chinese settled in Tibet, which is now modernised with apartment blocks, excellent roads (with surveillance cameras), and a railway linking Lhasa with Beijing and Shanghai. Although Tibet is now called, in Chinese, the “Xizang Autonomous Region”, the Chinese rule or oversee it with a heavy hand; the same goes for the various “Tibetan Autonomous Prefectures” in Amdo and Kham (within Qinghai and Sichuan Provinces) and two each in Gansu and Yunnan as well. As a rule, those autonomous prefectures represent little more than a symbolic cultural indulgence and in most of those ethnic Tibetans are now a minority. Meanwhile, the Central Tibetan Administration, based in Dharamshala (India), has proposed the “Umaylam” (Middle Way) Approach under the Tibetan leadership and His Holiness the Dalai Lama: to persist in seeking a peaceful solution through dialogue, bearing in mind both Tibetan and Chinese interests. For Tibetans, the Middle Way Approach implies not seeking independence but genuine autonomy within the framework of the People’s Republic of China. To date, the PRC has rejected any contact and is uncompromisingly hostile to any dialogue with the Tibetan diaspora. And all told, since 1949, more than 1.2 million Tibetans have died at the hands of the Communist Chinese.