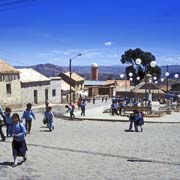

Photos of Potosí, the city built on silver, Bolivia

Potosí, the city built on silver

The discovery of ore in silver-rich Cerro Rico (“Rich Hill”) by Indian Diego Huallpa in 1544 prompted the foundation of the city of Potosí on 10 April 1545, which lies at the foot of the hill. Juan de Villarroel founded it as Villa Imperial de Carlos V in honour of the then Spanish King Carlos V.

you may then send it as a postcard if you wish.

The mine soon produced enormous wealth: most of the silver being shipped through the Spanish Main came from here. According to official records, 45,000 tons of pure silver were mined from Cerro Rico from 1556 to 1783, with 7,000 tons going directly to the Spanish monarchy. Indian labour, forced by Francisco de Toledo, Count of Oropesa through the traditional Incan mita institution of contributed labour, died by the thousands, not simply from exposure and backbreaking work, but by mercury poisoning as well: in the patio process, the silver-ore, being crushed to powder by hydraulic machinery, was cold-mixed with mercury and trodden to an amalgam by the native workers’ bare feet. The mercury was then driven off by heating, producing deadly vapours. Because so many indigenous labourers died, causing a shortage of workers, the colonists in 1608 requested the Crown in Madrid to import 1,500 to 2,000 African slaves per year. An estimated total of 30,000 African slaves were taken to Potosí throughout the colonial era. African slaves were also forced to work in the Casa de la Moneda as “acémilas humanas” (human mules). Since mules would die after a couple of months pushing the mills, the colonists replaced four mules with twenty African slaves.

After 1800 the silver mines became depleted, making tin the main product, eventually leading to a slow economic decline. Even now, the mountain continues to be mined for silver and tin to this day. Due to poor worker conditions (lack of protective equipment from the constant inhalation of dust), the miners still have a short life expectancy. Most of them contract silicosis and die around the age of 40. It is possible to visit the mines, which is an interesting and sobering experience, especially in the cooperative mines where one is led through the steep tunnels, deep inside the earth, and, being well over 4,000 metres above sea level, it is literally breathtaking!

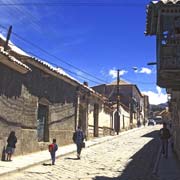

In 1672 a mint was established in Potosí to coin silver, and water reservoirs were built to fulfil the growing population’s needs. Potosí became one of the world’s largest cities with a population exceeding 200,000. Although it was 4,070 metres above sea level, it became a glittering town for the Spanish colonisers. The city had at one stage almost 90 churches. Many were looted, however, during the independence conflicts in the early 19th-century. But there are still many reminders of this era, colonial architecture with ornate churches and houses with balconies along narrow streets. Potosí’s Cathedral was built during the second half of the 16th Century and was finished in the early 1600s; it was reconstructed in the 19th Century. The San Lorenzo Church has mestizo-Baroque portal carvings by 16th-Century artisans, which are worth seeing. UNESCO declared the city of Potosí a “World Heritage Site” in December 1987 in recognition of its rich history and its wealth of colonial architecture. Potosí also has typical Bolivian music and dance on offer with the renowned folklore group Mosoj Ñan.

Twenty-five kilometres downhill from Potosí is Tarapaya with its thermal baths; it is surrounded by stunning scenery, notably Laguna Ojo del Inca (“The eye of the Inca”), a small lake set in a stark landscape.