Photos of the Culture of Mongolia

Culture of Mongolia

The culture of Mongolia is rooted in the nomadic way of life, going back thousands of years. Shamanism - the practice involving a practitioner reaching altered states of consciousness to encounter and interact with the spirit world - was the ancient religion of the Mongols and the peoples of Siberia and still has an influence. However, Tibetan Buddhism has been the dominant religion since the 17th century.

you may then send it as a postcard if you wish.

There are still shamanistic practices that have survived, like the rituals at the ovoo, a shamanistic cairn used in the worship of the mountains and sky; people may add rocks to the pile and leave behind offerings. A branch or stick may be placed in it, and a blue khadag, a ceremonial silk scarf symbolic of the open sky and the sky spirit Tengger, or Tengri, tied to the branch.

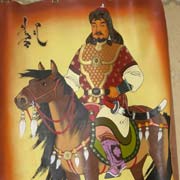

Both Buddhism and shamanism were suppressed in communist days but are experiencing a revival, and new Buddha statues have been erected and may be painted with gold coloured paint. Tibetan style stupas are placed near monasteries that have been restored or rebuilt. Thangkas or Tangka, a Tibetan silk painting with embroidery, are beautiful examples of Buddhist art, and there are many examples of wall paintings still to be seen in temples that were left standing. There are also paintings of the old Mongolian life of nobles and horsemen, and Mongolians love to dress in traditional costumes during festivals like Naadam.

A recurrent theme is the “Father of the Nation”, Chinggis Khaan (Genghis Khan); there are numerous depictions of him, in paintings and in statues, including the largest equestrian statue in the world, 40 metres tall and 250 tons of stainless steel at Tsonjin Boldog, 54 kilometres east of the Ulaanbaatar, where according to legend, he found a golden whip. Another hero, Damdin Sükhbaatar, the “Father of Mongolia’s Revolution” is honoured in paintings and statues while both may be displayed in parades, on horseback of course.

There are examples of ancient culture going back to the Bronze Age, like the famous “deer stones”, carved standing stones featuring flying deer in high relief, carved between 1500 and 800 BCE. An excellent example of these is within an emplacement of sacrificial mounds (“khereksuur”) in Uushigiin Övör, 20 kilometres west of Mörön.