Photos of Gallipoli peninsula, site of a World War I campaign, Turkey

Gallipoli peninsula, site of a World War I campaign

The Gallipoli peninsula (Gelibolu Yarımadası) is in the southern part of East Thrace, the European part of Turkey. To its west is the Aegean Sea and to its east the narrow Dardanelles strait, separating it from Asia Minor. The name “Gallipoli” is the Italian version of the Greek name Καλλίπολις (Kallípolis), “Beautiful City”, a town now known as Gelibolu.

you may then send it as a postcard if you wish.

The peninsula, known as Thracian Chersonesus, was settled in the 7th Century BCE by Greeks, who founded around 12 cities there. It became part of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire in 330 CE but was besieged and captured by the Ottomans in 1354, after a powerful earthquake had destroyed most of the city of Gallipoli. It was their first stronghold in Europe; between 1366 and 1376 it was recaptured for the Byzantines by Crusaders, but after that, it remained Turkish. Greeks, Armenians and Jews lived here, side-by-side with Turks. It all came to an end during the First Balkan War in 1913 when Ottoman troops destroyed, looted and burned Greek villages and murdered Greeks. The Turks tried to prevent Greeks to have a majority here if Thrace was declared autonomous after the war.

During World War I the Entente powers, Britain, France and the Russian Empire, tried to take control of the Dardanelles Strait to provide a supply route to Russia. It was part of a plan to also occupy Constantinople and weaken the Ottoman Empire, that had allied itself with Germany. It was Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty, who proposed a naval attack on the Dardanelles, expecting a quick victory. The Gallipoli or Dardanelles campaign started when on 19 February 1915 a strong Anglo-French task force began a long-range bombardment of Ottoman coastal artillery batteries. Although the Allies had booked some successes, they were frustrated by the mobility of the Ottoman gun batteries. The Turks managed to evade Allied bombardments and fired at minesweepers, sent to clear the Straits. Churchill urged increased efforts and the naval commander, Admiral Sackville Carden, telegraphed back that “they would be in İstanbul in 14 days”.

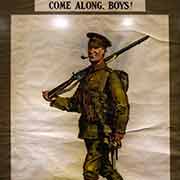

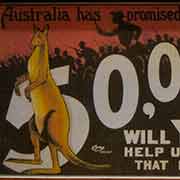

The Allies had underestimated Ottoman military potential because they felt superior. The Ottomans had German advisers. The Allies decided to land invasion forces on the peninsula, on the southern tip at Cape Helles and north of Kabatepe on the Aegean coast. The ANZACs, the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps, landed here at night on 25 April 1915. However, they went ashore more than 1.5 kilometres north of their intended landing beach. They became mixed-up and suffered casualties from Turkish defenders, but did form a beachhead, now called ANZAC Cove. The ANZACs had landed two divisions, but over two thousand of their men had been killed or wounded, together with at least a similar number of Turkish casualties.

In January 1916, after eight months’ fighting, with approximately 250,000 casualties on each side, the land campaign was abandoned, and the invasion force withdrew. It was a costly defeat for the Allies but considered a tremendous Ottoman victory. The prominent Ottoman commander had been Mustafa Kemal. Eight years later he won the Turkish War of Independence, declared the Republic of Turkey and became its first President. In Australia and New Zealand, the anniversary of the landings is still commemorated as ANZAC Day, at home and on ANZAC Cove. The Gallipoli peninsula has many wartime cemeteries and memorials of both sides and the “Gallipoli Kabatepe Simulation Centre” explains Gallipoli battles with panoramic displays, simulations and animations.