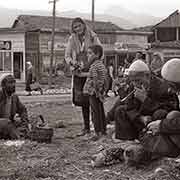

Photos from Kosovo

| Home | About | Guestbook | Contact |

KOSOVO - 1967-2018

A short history of Kosovo

Kosovo, the newest independent republic in Europe, has had a very complicated and violent history, especially in the years leading up to its independence. In ancient times it belonged to the Thraco-Illyrian tribes, the ancestors of the Albanians: in the 4th to 1st centuries BCE the Dardani inhabited the region which roughly corresponds to modern Kosovo. It then was part of the Roman, Byzantine, Bulgarian and Serbian empires. In the 13th century it became the secular and spiritual centre of the medieval Serbian state of the Nemanjić dynasty, with the Patriarchate of the Serbian Orthodox Church in Peć (Peja), and Prizren as the secular centre. In 1389 at Kosovo Polje (field of blackbirds), about 5 kilometres northwest from present-day Prishtina, Ottoman forces defeated a coalition of Serbs, Albanians, and Bosnians led by Prince Lazar Hrebeljanović. Serbia was reduced to a vassal state with Serbian nobles paying tribute and supplying soldiers to the Ottomans; Prince Lazar's daughter was married to the Sultan to seal the peace. By 1455 Kosovo was finally and fully absorbed by the Ottoman Empire. Although the Serbs were defeated, the Battle of Kosovo has become a symbol of Serbian patriotism. Its significance for Serbian nationalism returned to prominence during the break-up of Yugoslavia and the Kosovo War when the Serbian leader Slobodan Milošević invoked it during his speech in 1989, commemorating the 600th anniversary at Gazimestan, the monument to the battle.

Kosovo was part of the Ottoman Empire from 1455 to 1912, at first as part of Rumelia, and from 1864 as a separate province. During those years many Serbian Orthodox Christian families migrated out of Kosovo in addition to the forcible removal of Christian subjects by the Turks as slaves and war booty. In 1766 the Ottomans abolished the Patriarchate of Peć and non-Muslims became subject to taxation. Many Albanian chiefs, however, converted to Islam and gained prominent positions. During the four and a half centuries of Muslim rule, the number of Slavic Christians declined, while there was an inward migration of Albanian and other Muslim peoples. In the 19th century, there was an “awakening” of ethnic nationalism throughout the Balkans. Following the establishment of the Principality of Serbia, a meeting was held in Prizren in 1871. The possible retaking and reintegration of Kosovo and the rest of “Old Serbia” was discussed. In 1878, a Peace Accord was drawn that left the cities of Priština and Kosovska Mitrovica under Serbian civilian control, while the rest of Kosovo remained under Ottoman control. The ethnic Albanian nationalism movement also centred in Kosovo: on 10 June 1878, the League of Prizren was founded. It aimed to prevent the Albanian lands from being annexed by Serbia and Montenegro. Montenegro claimed northern Albania and the Metohija region, encompassing Peja, Gjakova and Prizren) and to seek autonomy under the Ottoman Empire. The movement was put down by the Turks in 1881; there were further uprisings until finally in 1912 a provisional government was proclaimed in Vlora (Albania) by Ismail Qemali.

That year most of Kosovo was captured by the Kingdom of Serbia, while the Kingdom of Montenegro took the region of Metohija. Serbian and Montenegrin soldiers started a furious campaign of murder and plunder in the Albanian regions; resistance was smothered in blood in 1912-1913 and later in 1918-19. The local Albanian population was driven out while Serbian authorities promoted creating new Serb settlements in Kosovo with many Serb families moving in. In 1913 the Great Powers acceded to Serbian demands that Kosovo, about one-third of Albanian territory, was transferred to their control. 1 December 1918 the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was formed, later renamed the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Large-scale Serbian colonisation of Kosovo was undertaken by the Belgrade government between 1912 and 1941 to change the ethnic composition of Kosovo. Meanwhile, Kosovar Albanians' right to receive education in their language was denied. In 1941 the Axis powers invaded Yugoslavia; large parts of Kosovo became part of Italian-controlled Albania; other parts went to Bulgaria and German-occupied Serbia. The Italian Fascist regime of Benito Mussolini exploited the nationalist sentiment amongst Albanians. It attempted to gain favour for the Italian-run protectorate which ruled Albania and thus encouraged the establishment of a Greater Albania which included large portions of Kosovo. Tens of thousands of Serbs were driven out of Kosovo during this time. In 1944 the Kosovar communist resistance leaders passed a resolution on the postwar assignment of Kosovo to Albania, but their opinion was later disregarded. Kosovo was eventually liberated in 1944 with the help of the Albanian partisans of the Comintern and in 1945 became a province of Serbia within Democratic Federal Yugoslavia as the Autonomous Area of Kosovo-Metohija.

The harsh repression and forced expatriation of Albanians resumed under Tito until July 1966 when Yugoslav Interior Minister and Vice President Aleksandar Ranković was ousted. He had been instrumental in the brutal treatment of Kosovar Albanians. Kosovo gained limited internal autonomy as the Autonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija. During the 1970s it received more autonomy and self-government within Serbia and Yugoslavia. Its name was officially changed in 1974 to “Socialist Autonomous Province of Kosovo”. The name “Metohija” was removed because the Kosovo Albanians disliked it: Metohija, meaning “Monastic Estates” in Greek, refers to a large number of villages and estates in the region that were owned by Serbian Orthodox monasteries; in Albanian it is called “Rrafshi i Dukagjinit”, Dukagjini Valley, after the governing family of the area, going back to the 13th century). The province received a seat in the Federal Presidency which made it a de facto Republic within the Federation but remaining a Province within the Socialist Republic of Serbia. Serbo-Croat, Albanian and Turkish were defined as official languages in the province. Due to very high birth rates, the number of Albanians increased from 75% to over 90%. The number of Serbs dropped from 15% to 8% of the total population, since many Serbs departed from Kosovo as a response to the tight economic climate and increased incidents of alleged harassment from their Albanian neighbours. While there was tension, charges of “genocide” and planned harassments have been debunked as an excuse to revoke Kosovo’s autonomy. For example, in 1986 the Serbian Orthodox Church published an official, though false, claim that Kosovo Serbs were subjected to an Albanian program of “Genocide”. Even though this was disproven by police statistics, it received much publicity in the Serbian press, and that led to further ethnic problems and eventual removal of Kosovo’s status.

On 28 June 1989, Slobodan Milošević delivered a speech in front of a large number of Serb citizens at the main celebration marking the 600th anniversary of the Battle of Kosovo at the Gazimestan monument. The same year Milošević, employing a mix of intimidation and political manoeuvring, drastically reduced Kosovo's special autonomous status within Serbia and started the cultural oppression of the ethnic Albanian population. Kosovo Albanians responded with a non-violent separatist movement. They employed widespread civil disobedience and created parallel structures in education, medical care and taxation, with the ultimate goal of achieving the independence of Kosovo. On 2 July 1990, an unconstitutional Kosovo parliament declared Kosovo an independent country, the Republic of Kosova. On 2 September 1991, after some of the Republics of the former Yugoslav federation declared their independence, the Parliament of the Republic of Kosova adopted the Resolution of the Independence that proclaimed it as a Sovereign and Independent State. In May 1992, Ibrahim Rugova was elected president. During its lifetime, the Republic of Kosova was only recognised by Albania. Meanwhile, Yugoslavia was disintegrating. The Dayton Agreement of 1995 ended the Bosnian War, but, despite the hopes of Kosovar Albanians, the situation in Kosovo remained largely unaddressed by the international community.

In 1996 the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA), an ethnic Albanian guerrilla group, had prevailed over the non-violent resistance movement. It had started offering armed resistance to Serbian and Yugoslav security forces, resulting in the early stages of the Kosovo War. By 1998, the violence had worsened, scores of Albanians were displaced, and finally, Western interest increased. The Serbian authorities were compelled to sign a ceasefire and partial retreat, but the truce did not hold, and fighting resumed in December 1998. The Račak massacre in January 1999, in particular, brought new international attention to the conflict. The Rambouillet Accords were signed, calling for the restoration of Kosovo's autonomy and deployment of NATO peacekeeping forces. The Serbian party refused to sign the draft. NATO forces bombed Yugoslavia between 24 March and 10 June 1999, aiming to force Milošević to withdraw his troops from Kosovo. The bombardments with continued skirmishes between Albanian guerrillas and Yugoslav forces resulted in further massive displacement of population in Kosovo. During the conflict, roughly a million ethnic Albanians fled or were forcefully driven from Kosovo; more than 11,000 deaths were reported. By June Milošević had agreed to a foreign military presence within Kosovo and withdrawal of his troops. Some 200,000-280,000 Serbs, representing the majority of the Serb population, left when the Serbian forces left. There was some looting of Serb properties and violence against some of those Serbs and Roma who remained.

Since May 1999, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia has prosecuted crimes committed during the Kosovo War. Nine Serbian and Yugoslavian commanders were indicted for crimes against humanity and violations of the laws or customs of war in Kosovo in 1999; Milošević died in custody during the trial in 2006. They directed, encouraged or supported a campaign of terror and violence directed at Kosovo Albanian civilians and aimed at the expulsion of a substantial portion of them from Kosovo. It has been alleged that about 800,000 Albanians were expelled as a result. After the Kosovo War, the territory came under the interim administration of the United Nations (UNMIK). In 2000 the “Republic of Kosova” was therefore disbanded. Kosovo held its first free, Kosovo-wide elections in late 2001. International negotiations began in 2006 to determine the final status of Kosovo. The UN-backed talks, led by UN Special Envoy Martti Ahtisaari, opened in February 2006. In February 2007, Ahtisaari delivered a draft status settlement proposal to leaders in Belgrade and Prishtina, the basis for a draft UN Security Council Resolution proposing ‘supervised independence’ for the province. Serbia, backed by Russia, refused to consider any form of independence for Kosovo.

Nevertheless, on 17 February 2008, the Assembly of Kosovo declared independence as the Republic of Kosovo. 57 UN member states recognised the new state’s independence at the end of the year. A majority of countries took the Serbian position, viewing Kosovo as a UN administrated province of the Republic of Serbia. However, all of Kosovo’s immediate neighbour states except Serbia, have now recognised Kosovo’s independence. In 2018, the Republic of Kosovo had received 115 diplomatic recognitions as an independent state, but 10 were subsequently withdrawn. In April 2013, Kosovo and Serbia reached an agreement to normalise relations, and thereby allow both nations to eventually join the European Union. Under the terms of the agreement, “Belgrade acknowledges that the government in Priština exercises administrative authority over the territory of Kosovo - and that it is prepared to deal with Priština as a legitimate governing authority”. A promising development, as Serbia now starts to realise that in light of the past it is inconceivable that the majority Albanian population would consider being ever under Serbian rule again...

...The black-and-white photos were taken in 1967 and 1969 when the country was peaceful, and the events of 30 years later were unthinkable. Thanks to Jan Schmetz, who kindly permitted to use some of his photos, as indicated....