Photos from Bhutan

| Home | About | Guestbook | Contact |

BHUTAN - 2023

A short history of Bhutan

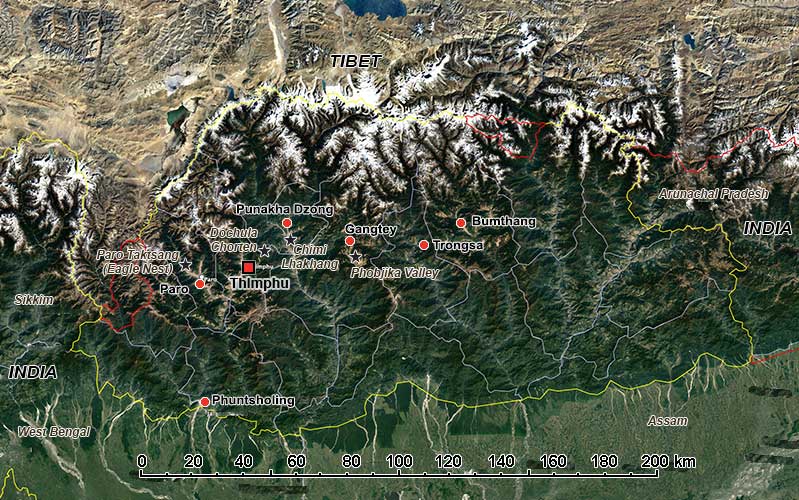

The Kingdom of Bhutan is a small country in the Eastern Himalayas, between Tibet in the north and northwest, the Indian states of Sikkim in the west, West Bengal and Assam in the south, and Arunachal Pradesh in the east. It has an area of around 38,400 km², although China, occupying Tibet, claims some regions in the west and north (disputed borders are indicated in red on the map above). Its population is around 730,000. Throughout history, Bhutan has always been independent and has never been conquered or occupied. Archeological finds indicate that present-day Bhutan was already inhabited around 4,000 years ago. It is possible that between 500 BCE and 600 CE, a state existed referred to as “Lhomon” or “Monyul” (Southern Darkness or Dark Land), which seems to refer to the Monpa, a Tibeto-Burman people who also live in the northwest of Arunachal Pradesh.

In the seventh Century CE, Buddhism was first introduced to Bhutan from Tibet; the Tibetan king Songtsän Gampo, who ruled from 627 to 649), ordered the construction of two Buddhist temples in the country. The Bon or Bön indigenous Tibetan religion, also prevalent in Bhutan, was absorbed into Buddhism. In 810 CE, a Buddhist saint, Padmasambhava, also known as Guru Rimpoche, came to Bhutan from India at the invitation of the king of Bumthang, one of the numerous local kingdoms; there was no central government at the time. He converted the king, moved on to Tibet, and, upon returning, oversaw the construction of new monasteries and the founding of the Nyingmapa (or “Red Hat”) sect of Mahayana Buddhism. Later, the Drukpa branch, introduced from Tibet, became dominant in Bhutan, and one aspect of this was the construction of “dzongs”, fortified monasteries.

In the 17th century, a theocratic government independent of Tibetan political influence was founded by Ngawang Namgyal, a Drukpa monk, who arrived in Bhutan from Tibet in 1616. He sought freedom from the domination of the Gelugpa (“Yellow Hat”) subsect that the Dalai Lama led in Lhasa. Ngawang Namgyal united the leaders of powerful Bhutanese families. From that time, the land was called “Drukyul”, “Land of the Drukpa Lineage”, or “Land of the Thunder Dragon”, which remains to this day the native name of Bhutan. Under his rule, a code of law and network of forts, Dzongs, was built. It brought local rulers under centralised control and defended the country against invasions from Tibet: throughout the first half of the 17th century, Tibetan armies, sometimes in alliance with Mongol forces, invaded to dethrone Ngawang Namgyal and re-establish Gelugpa dominance, but they were ultimately defeated.

From the late 17th until the early 18th century, there were conflicts with Tibet, and Sikkim and Bhutan even assisted Ladakh (now a territory in northwestern India) in its war with Tibet in 1684; Ladakh had even granted Bhutan enclaves in western Tibet. But in 1772, it got into conflict with the British, who were now starting their dominance over India. They signed a Peace Treaty with the British East India Company and withdrew from areas they had occupied. Over the years, boundary disputes remained between the Bhutanese and the British, who now represented a more significant threat to Bhutanese sovereignty than the Tibetans.

In the late 19th century, a rivalry developed between two “Penlops” (provincial governors), the pro-Tibetan Penlop of Paro in western Bhutan, and the pro-British Penlop of Trongsa, in central Bhutan, Ugyen Wangchuck: he proceeded, after a series of rebellions and even civil wars between 1882 and 1885, to defeat his rivals and unite the country. The British wanted to open trade relations with Tibet (to thwart potential Russian advances there), and Ugyen Wangchuck volunteered to accompany a British mission to Lhasa as a mediator in 1903. The British knighted him, and he became the most powerful leader in Bhutan.

Bhutan, until that time, had been ruled by a dual political theocratic system, in which government authority was divided among secular and religious administrations, both unified under the nominal authority of a “Zhabdrung”, High Lamas, considered reincarnations of Ngawang Namgyal (1594–1651), the founder of the Bhutanese state. At the start of the 20th century, it was realised that this system was obsolete and ineffective, and after the death of the last Zhabdrung in 1903, the system ended. In November 1907, an assembly of leading Buddhist monks, government officials, and heads of important families decided to abolish it and establish a new absolute monarchy with Ugyen Wangchuck as the first hereditary “Druk Gyalpo” (Dragon King).

Britain welcomed this development in neighbouring British India, as it would stabilise their shared border. China, still under the Qing dynasty, had sent troops into Tibet to assert imperial authority, forcing the Dalai Lama to flee to India. China claimed not only Tibet but also Nepal, Sikkim and Bhutan. The British signed the Treaty of Punakha on 8 January 1910 through their Political Officers in Sikkim and Bhutan. It amended an earlier treaty of 1865 and stated that, for an annual stipend of 100,000 rupees and the plea of no interference in its internal administration, Bhutan agreed “to be guided by the advice of the British Government regarding its external relations.” It meant that Britain would defend Bhutan against Chinese aggression while Bhutan was guaranteed its independence: one of very few Asian countries never to be colonised.

Under the rule of Ugyen Wangchuck, the first Druk Gyalpo, western-style schools, improvements in communications and trade with India developed in a program of modernisation. He died in 1926 and was succeeded by his son, Jigme Wangchuck, who reigned as the second Druk Gyalpo until 1952. He continued the modernisations his father had started; more schools, clinics and roads were built, while monasteries and district governments were increasingly under royal control. Bhutan, however, remained an isolated country that was virtually unknown to the outside world.

In 1947 India became independent and succeeded Britain as Bhutan’s de facto protector. India and Bhutan signed a Treaty of Friendship on 8 August 1949. India recognised Bhutan’s independence and increased the annual subsidy to 500,000 rupees, while Bhutan agreed that India guided its external affairs. In 1952, Jigme Wangchuck died and was succeeded as the third Druk Gyalpo by his son, Jigme Dorji Wangchuck. One of his first reforms in 1953 was the establishment of the “Tshogdu”, the National Assembly, a significant move toward a constitutional monarchy. During his 20-year reign, he was the driving force behind the fundamental reorientation of Bhutanese society.

In 1951, Chinese communists took over Tibet, and Bhutan closed its northern border, siding with India; a modernisation program implemented land reforms, abolition of slavery and serfdom (as had existed before, as in Tibet) and roads constructed between Bhutan and India, especially after the Tibetan uprising against the Chinese in 1959. Punakha Dzong had been the administrative centre and seat of Government until 1955 when Thimphu replaced it; in 1961, the king declared Thimphu as the capital of the Kingdom of Bhutan. In 1971, Bhutan became a member of the United Nations.

Jigme Dorji Wangchuck ruled until his death in July 1972 and was succeeded as the fourth Druk Gyalpo by his seventeen-year-old son, Jigme Singye Wangchuck. He was formally coronated two years later. Under his rule, the country strove to retain its culture, crafts, beliefs, customs and languages; he emphasised the distinctive characteristics of Bhutanese cultures while speeding up reform and modernisation. On 15 December 2006, the fourth Druk Gyalpo, Jigme Singye Wangchuck, abdicated his powers as King to his son, Prince Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck. He intended to prepare the young king for the country’s transformation to a full-fledged, democratic form of Government in 2008.

On 6 November 2008, Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck was officially crowned in Punakha in an ancient and colourful ritual. He implemented still further democratisations and has proved himself very popular at home and abroad. Bhutan is a beautiful country to visit, but tourists may only do this on a guided tour with a driver and guide, making it an expensive proposition. But it means the country doesn’t suffer from being over-touristed and guests are well looked after. The Government tries to uphold the phrase’ gross national happiness’, which was first coined by the fourth King of Bhutan, King Jigme Singye Wangchuck, in the late 1970s when he stated, “Gross National Happiness is more important than Gross Domestic Product”, implying that sustainable development should give equal importance to non-economic aspects of wellbeing and happiness. Traditional clothing is worn by many and is obligatory for official functions. Bhutan, although modernising, remains faithful to its unique culture.