Photos from Afghanistan

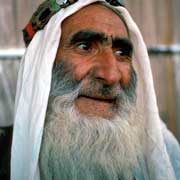

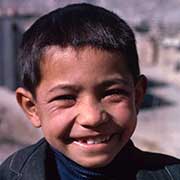

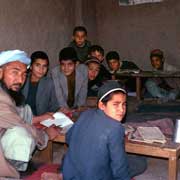

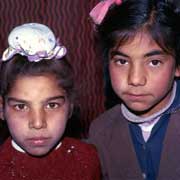

The people of Afghanistan

Afghanistan is a multi-ethnic country, including peoples who also live in neighbouring countries. The Pathan (Pashtun or Pashto) people are traditionally the dominant ethnic and linguistic community. They are concentrated in the east and the south, although now many are settled in other areas as well. Pashtuns also dominate the neighbouring tribal regions of Pakistan.

you may then send it as a postcard if you wish.

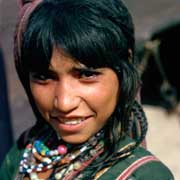

Tajik people who speak Dari (a Persian dialect) live mostly in the eastern valleys north and south of the Hindu Kush mountains and in Tajikistan to the north. Dari is the most widely spoken language in Afghanistan and the mother-tongue of approximately 50%. Turkic peoples, mostly Uzbek and Turkmen, live in the northern plains as farmers and herders and also in the republics of Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. The Hazara, a Mongoloid people who mostly speak Persian, live in the central mountains and there are many smaller communities, like the Nuristanis of the high peaks of the northeast and the Baluch who live in the southern desert and the neighbouring Baluchistan region in Pakistan. There are three million Kuchis (from the Persian word Koch meaning “migration”) in Afghanistan, Pashtun nomads. The women do not wear the all-enveloping “chaderi” or “burqa”. At least 60% Kuchi remain fully nomadic; they have however suffered greatly in the past two decades of war and destruction; for most Kuchi life means poverty, war, shrinking access to land, ethnic tensions and leftover land mines.

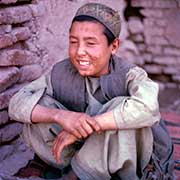

The people of Afghanistan are a tough, hardworking people, living in a magnificent but harsh country. They are dignified, fiercely independent, but very hospitable and courteous to strangers in their splendid time-honoured Muslim tradition. Life is hard for many in this country of extreme temperatures, hot in summer, icy in winter. Farming is hard work, dealing with dry, sunbaked soil that must be broken up with wooden ploughs, pulled by oxen. In small workshops all over the country, people make long hours, and work is all manual. Yet, objects of great beauty are produced in wood, brass and textiles.

For many children theirs is a working life too; although there is no doubt they are loved and valued like everywhere else, quite often parents cannot afford to send their children to school and boys have to help out on the field or in the workshops where they learn the trade from their fathers. Others earn their keep running errands, acting as porters or shining shoes. They are resilient and are expected to contribute to the family at an early age, may put in long hours in often harsh conditions, but it is clear the boys grow up to be tough men. In this strictly Muslim country, girls are usually confined to the house, so it is mainly boys you see on the streets. They work and play, and always seem cheerful, friendly and courteous to strangers.